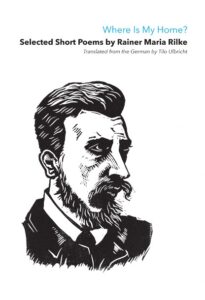

A Review

Can poetry be translated? Is it actually possible to translate a poem into another language since the precise words used, their meaning, their etymology, their syllables, their very sound, are all integral to the effect of the poem? Surely something must be lost in translation: either the meaning, or the poetry. . . perhaps both at times! Over the last few months I have been reading Tilo Ulbricht’s recent translation of some of Rilke’s short poems which appear to have overcome this particular difficulty.

They read as poems in their own right and have been a revelation. Previously I had rather dismissed Rilke’s short poems, because the translations I had read seemed rather flat and insubstantial. Many people have commented on the difficulty of translating Rilke since his poetry relies so much on the sonic effect of the words, their rhythm and rhyme. And then Rilke writes about inner experience with great subtlety, using metaphor and image. This presents a huge challenge to the translator.

These new translations are vivid and alive, they bring me a sense of kinship with the poet, and a marvelling: how did he know? For example:

‘But we are – yet hardly different from lambs;

days pass us by, lost in flight and in appearances;

like them, when twilight returns to our meadow,

we long to go back – but no one drives us home.’ (No.28 But we are. . .)

Or

‘Who are you, spirit beyond my understanding?

How do you know where and when to find me,

to penetrate that which was hidden with such light

that what was fragmented is made whole?’ (No.34 The Scent)

Rainer Maria Rilke, (1875-1926) acknowledged by many as one of the finest German-language poets, is widely read in Germany and elsewhere on the continent, yet is hardly recognised in Britain. He is best known for his Duino Elegies, a series of ten long poems written over ten years. They are difficult, complex poems which take time to appreciate. The shorter poems in this volume offer a more immediate way into Rilke’s world. He used a poetic language of metaphor in which the same images and metaphors recur repeatedly. To read his work is to enter a poetic landscape which has a dreamlike quality where one cannot tell whether he is speaking about reality or symbol: do his love poems address a real woman, or an ideal, or ‘the Beloved’; are the seasons those of the passing year, or those of his passing life, or those of the soul?

Tilo Ulbricht is perhaps uniquely qualified to translate Rilke, a German by birth, he has lived most of his life in England, so is fluent in both languages. He is a poet in his own right, having written for over eighty years (a selection of his own poems has been recently published). And finally, having himself followed an inner way throughout the majority of his life, he is particularly fitted to understand and interpret the esoteric nature of Rilke’s poems into English. In the introduction he says that he views a poem as already being a translation from the ‘formless into word form. . . . so the translator, guided by the words of the poem, needs to listen inside to the sound from which the poem was born.’ He must follow in the footsteps of the poet, not just understanding the meaning of the poem, but in a sense, living it, so that he can recreate the poem in the new language.

This might suggest that the translations will deviate far from the German text, however the poems mostly stay close to the German original, and their meaning is clear, limpid even. I do wonder if sometimes it is too clear; German speakers tell me that in the original poems the meaning is more elusive. This volume helpfully provides the German text alongside each translation, so bilingual readers can make the comparison. There are a few poems, such as No.43, “One must die because one knows them” which depart substantially from the original, in order according to Tilo Ulbricht, to convey more exactly the feeling of the original poem. This strange poem seems to me to convey something of the overwhelming power of the feminine on men. For me this is one of the less successful translations, however that could be because I cannot relate to it.

“One must die because one knows them”

‘Die from a flowering of smiles we cannot

describe. Die from their delicate hands.

Die from women.’

Already I have favourites which I return to again and again, particularly No.11 ‘What of the enemy. . .’ with its marvellous and awful final image of God as ‘that great breaker-down of walls.’ Or the Annunciation (No.25) in which the angel speaks to Mary:

‘Now you are more alone than ever

and hardly look at me;

I am just a breath in the wood.

But thou, thou art the tree.’

So, if you have never read Rilke, do buy this charming little book, just the size to slip into a pocket or bag.

Anne Humphreys