June is already more than half over, and summer almost officially declared, even though the weather remains cool and unstable. The summer solstice will be celebrated by the “fête de la musique”, inaugurated some twenty years ago by the charismatic socialist minister of culture Jack Lang. All over Paris there will be free open-air concerts of all kinds of music, from huge gatherings in the Place de la République to more intimate settings such as street corners. It has established itself as a regular fixture in Paris and throughout France. As every year however a whole group of young people will be excluded from the festivities, because another no less regular feature of French life in this month of June is the national exam known as the Baccaluréat or the bac.

There are other reasons to make this the subject of my letter this month. As in other countries, no doubt, but for specific reasons peculiar to France, the “crisis” in education is a recurrent subject of discussion. That there is a crisis is the only point on which everyone is agreed. Its precise nature, scope and the solutions offered are endlessly debated. (For example, when a French film* about life in a secondary school – incidentally not far from where I live – partly fictional, but using children and teachers as actors, won the coveted Palme d’Or at the last Cannes film festival, the award was greeted by a controversy about the state of French education.) For what it’s worth, as far as the national education system is concerned, my own view is that it is far too late for surgery and that a bomb is the only solution – but in that I’m probably in a minority of one.

It would be impossible – and inappropriate – to attempt a discussion of the whole system, but the “bac” deserves particular attention for at least two reasons. First, because almost everyone agrees that it is unsatisfactory. The president has recently announced his intention to reform it but given the nature of the system nothing can really be achieved until 2011 – just before the next presidential election, and my own guess is that nothing will come of it. (The state of governance in France, particularly under the new president, could be the subject of a future letter.)

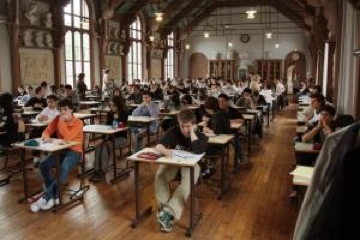

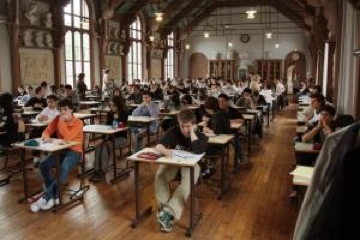

The second reason to make the “bac” the subject discussion this month is because 2008 marks to 200th anniversary of its foundation – typically by a decree by Napoleon. Since then, of course, there have been numerous changes, but it remains in certain respects what it has always been: the bac provides access as of right to higher education. In the current situation, with a success rate of over 80%, such a “right” is of dubious value. In fact, if one adds those who retake the exam, it has been estimated that the pass rate is almost 100%, and since school education has been prolonged it means that a far larger proportion of the age group take the exam – this year there will be 615,000 candidates – which is thus in part transformed into a leaving certificate, showing little more than the satisfactory completion of secondary education, which is why it is frequently said that the bac is worthless, but that not to have it is a disaster.

So what is it exactly? As usual in France, it is highly complex, baroque or even Byzantine in its structures and rules. In its academic form there are three options: literary, scientific and economic. Each option stipulates a certain number of subjects, each of which has varying “coefficients”, or weighting. So, in one option, Philosophy will have a coefficient of 7, while in others it is 4, 3 or even less. Marks for each paper (always out of 20) will be multiplied by the coefficient before all the marks are averaged. The final average of all subjects gives the result, with a pass mark of 10. Below 8 is a fail; between 8 and 10 candidates can take oral exams to pick up extra marks. From 12 to 14 candidates have a “mention”; from 14 to 16 “mention bien” and above 16 “mention très bien”.

As I said, to have the bac gives the candidate the right to a place in a university, but those with the highest marks, especially “mention très bien” do not take this route. Instead they apply for a place in a lycée (the more famous the better) for a two-year course preparing for competitive exams to gain entrance to one of the “grandes écoles”: “Nomale Sup” for academic subjects (roughly equivalent to what Oxford and Cambridge used to be in the English context); high-level engineering schools, such as les Mines, Ponts et Chausées, or Polytecnique; or Sciences-Po followed by ENA for the highest administrative positions. The laureates of these “grandes écoles” form the elite of French society. For example, Nicolas Sarkozy is the first president of the 5th republic – founded in 1958 – who has not emerged from this background (he is a lawyer and an opportunistic career politician). I can think of only one prime minister during the same period (Pierre Bérégovoy) who was not a graduate of a “grande école”. Not only that, graduates of the most prestigious institutions – especially ENA (l’Ecole Normale de l’Administration) – become members of a powerful network, which operates for the rest of their lives. Despite the notion formulated by Napoleon of a career open to talent – a meritocracy, it is well known that students at these schools are overwhelmingly from families in which at least one parent was also a graduate: the elite is self-perpetuating.

But what of the rest? The scope of the bac has been widened, with professional and technological subjects, for example. Although these were initially intended to be vocational courses, whose graduates would go straight into employment, employers quickly demanded further years of study with the result that these students too began to join the ranks of those applying for further education – primarily universities. The problem is that the universities are hopelessly stretched. Numbers of students in the first two years are impossibly high, so that there is often not enough room in lecture halls. Students are offered little guidance in the choice of subjects, and after two years almost half are eliminated, entering the employment market with nothing tangible to offer.

An essential factor in this situation is that universities do not select their students – selection is delayed until the end of the second year, with disastrous results. Attempts to introduce selection at the point of entry are fiercely resisted, by both students and (with rare exceptions) universities. It is characteristic of the national education system that it contains numerous interest groups which cling to their privileges and maintain the status quo against all the odds – which is why I think a bomb is the only solution! For example, there is a policy of encouraging, and even obliging, pupils to re-do a year if their results have been poor. France is, as far as I am aware, the only European country to have such a practice. Despite research, (some conducted by the ministry itself) which indicates that repeating the year is ineffective as well as very costly, attempts to abolish the policy are resisted (mainly by teachers) and the system rolls on.

Teachers are poorly paid, demoralized but monolithically conservative. The recruitment of teachers is through a competitive exam, with numbers accepted for each subject determined by the ministry. Once accepted however, it is virtually impossible to dismiss a teacher. There is no department structure in schools and teamwork is rare. The private sector is growing, for those who can afford it, and on the metro one can see adverts for private tutor organisations which seem to have mushroomed in recent years – surely a symptom of a malaise.

Education has often been vaunted as the way to social mobility. (There is a Jewish joke here: question – what is the difference between a tailor and a dentist? Answer: one generation. This may once have been the case, but it is no longer.) Generations of children of North African origin worked hard for their bac and saw that it led nowhere. Their younger siblings have learned the lesson and are dropping out, with alarming consequences. For the privileged elite the system continues to operate as of old, but for the most part it is a classic case of a dysfunctional system that is unable to change.

Julian Arloff