My wife and I recently visited Prague for a few days, a city which we had both wanted to see for many years. We were continually surprised by the vivid combination of historic buildings, beautiful hillside parks, genuinely welcoming local people, the variety of music and hearty food and drink. But I was not prepared for the shock of visiting the Pinkas Synagogue, part of the Jewish Museum.

From 1941, over 80,000 Jews were rounded up from Prague and the surrounding areas and transported to a holding camp north of the city at Terezin. This number included approximately 10,000 children. Some idea of the conditions that the inhabitants had to endure can be understood from knowing that when the site was previously used as an army barracks, between 3,000 and 6,000 troops were accommodated. More than 33,000 prisoners died there. Throughout 1944, most of the inhabitants of the camp were systematically deported to Treblinka and Auschwitz where the vast majority were murdered.

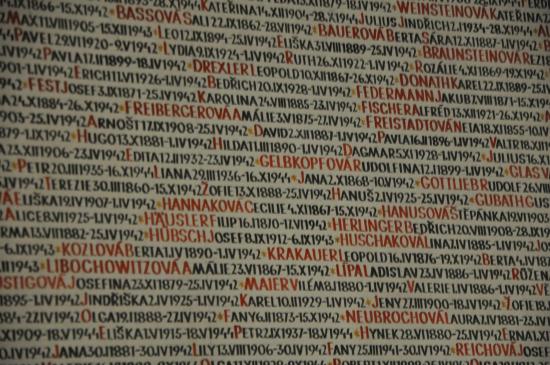

The Pinkas Synagogue has the name of every single Jewish Prague citizen who was deported written on the walls. Each person has their name, date of birth and date of deportation recorded. An old and much missed friend of ours, Bob Schuck, founded a project called Postcards from Europe to commemorate musicians and composers who were imprisoned and killed during the Holocaust by discovering and performing their music. His passionate commitment to this cause (brought to a premature end by his untimely death at the age of 58) was fired by many of his own family having been killed. We found their names on the walls, and remembered Bob, who was himself a supremely gifted musician and linguist.

Old, middle-aged, young, children – from ten days old to over eighty. My eyes were caught by individual names, families, accompanied by an increasing sense of inner anger, sandwiched between appreciation for these people not being forgotten and not wanting to be disturbed from my usual complacent state.

But even this experience was overshadowed by the impressions received from a small exhibition of drawings and paintings by children from the Terezin camp. They were given art classes by Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, an artist and teacher who was deported to the camp in December 1942 and lived there with her husband until being transported to Auschwitz in September 1944 where she died the following month. One can gauge something of her energy and drive from what she wrote to a friend in 1940.

“I remember thinking in school how I would grow up and would protect my students from unpleasant impressions, from uncertainty, from scrappy learning. Today only one thing seems important — to rouse the desire towards creative work, to make it a habit, and to teach how to overcome difficulties that are insignificant in comparison with the goal to which you are striving.”

By encouraging the children to draw to express their feelings, she found a way to help free themselves if only a little from their desperately difficult circumstances. To describe any of these drawings would in a way be a sacrilege. They are so personal, so simple and so shocking – imploring you to sense your own humanity again, to strive for something more than just reacting to events, that words fail. The only reason they survived is that once Dicker-Brandeis knew she was being deported, she hid two suitcases containing over 4,000 of the childrens’ drawings. On a poignant note, she painted and drew almost continuously during her last two months at Terezin, and not one of her chosen subjects was the camp itself, but celebrations of life – landscapes, nudes and portraits.

It seems particularly appropriate on the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz to remember this selfless and brave woman.

Geoff Butts

The web site for Postcards from Europe can be found here. http://www.postcardsfromeurope.co.uk/Postcards/HOMEPAGE.html