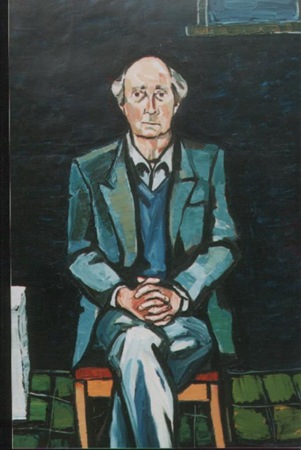

I was touched to hear John McGahern speak in the Purcell room at London’s South Bank in October 2005.

He read from his remarkable Memoir, was interviewed and accepted questions from the audience. Afterwards he stood quietly as a long queue of people came to him for his signature to be placed upon purchases of his newly published and last book.

I sat to one side and watched as he gave to each and every one that approached him. I do not, because he has died, embroider that; for it was such an individual communal attention drawn from his own individuality and his people. Few of the many Irish writers that I have read have portrayed so finely that ‘rocky road to Dublin’ Ireland now gone; yet in a subtle way still there among the drizzle, lengthening motor-ways, Africans in Clonakilty, Poles in Tipperary, euro zone, glamour, stark housing estates, and the darkness that exists inside.

Ireland, the mythological land between the no-places, enclosed within the 9th wave, from which came the waitering bricklayers of New York, Sydney and Godot. Talking of DeValera, Collins, Archbishops and Holy Communion. The Irish abroad who sought their homeland in Dagenham, the Bronx, Paris, and in the dry, crusted grain fields of New South Wales.

A question is posed from the audience, Why was he not bitter? He moves through a long pause, his thin frame of sensitivity; with a tilt of the head he quietly replies, “Bitterness is a failure of the intellect”.

That night too, a different audience from the many that I have witnessed on my ‘Irish Travels’ across the layers of migration. Nights of attendance inside Los Angeles and Melbourne, London and New York; Irish nights; visiting writers from home, musicians, dancers. A difference from those who read the Tipperary Star, Cork Examiner, The Kerryman, from home; come home, going home, leaving home. We had great ‘craic’, you’re cracked, said the poor migrants pissed drunk to soaking wet pants on the night boat to Liverpool.

Tears and laughter as with ships passing in the night observes the audience slowly, almost imperceptibly reshaping and sitting in the shadows of Purcell were French, Spanish, Italian, Americans, Dutch, English gentry, new Irish, secure Irish, proud Irish, and in the minority a few life-shrunken London Irish spotted in their seats, desperately yearning for a place of recognition; placing, the placing me, the placing of me, mind body feeling and emotion.

Growing old abroad between the waves of memory; practicing to let go. And the Irish Times I still read Saturday cover to cover. Ireland and John McGahern.

I have a photograph, an old one-not that anything is really old or young. There in the bog 1955 my mother, two of my sisters, two of my brothers, and I or is it me separating out? It is summer. The Mother wears a dress, the boys in short breeches. I remember that afternoon… no, I am remembered to a few moments of it, which leads me to believe it all happened. The sun shone the heather was warm, but I feel as I felt as a child that as it happened it didn’t happen. This feeling haunted me, a child.

And now?

I read his novels:

The Barracks (there is one in every village)

The Dark

Amongst Women

That They May Face the Rising Sun

and the autobiography

Memoir (an unsentimental search for an essential voice).

The composition of an ‘Irish life’ was in part written and unwritten by John McGahern and I suppose in a way that is why when I heard of his death I felt such unexpected tears.

For although mine, none of it is mine, it is all given, all is known completely known yet completely utterly unknown. Is it true or another great piece of the crack that the Buddha spoke “All is illusion”?

And Patrick the ‘chosen fool’ heard Glor na gael in his elemental eternal dream call him

“We request you, holy boy, that you come and walk once more among us”.