When I was in my early fifties I took early retirement from the work I had been in for almost thirty years. All my career I had worked for a major public art gallery and had enjoyed the challenges of a number of varied and stimulating roles within the institution, ending up leading the exhibitions department. But I became aware that I was repeating myself, treading water. In a word I felt stuck. I could see that circumstances were not favourable for my future development, that there were fewer opportunities for new initiatives and the arrival of a new director was not likely to improve the situation. I made one or two attempts to apply for positions elsewhere but my heart was not in it. I sensed that other, younger applicants had the edge in terms of new ideas and drive. And so when the opportunity came to take early retirement I didn’t hesitate. My daughters had grown up and were living independently and I was confident that my wife and I would manage.

The question that faced me, as it must many others, was what would I do. I was not yet old and enjoyed good health. How would I occupy myself? For a time I undertook a number of consultancy roles for museums and galleries, partly from a sense that I ought to continue to work and earn. While this work was stimulating intellectually and meant I was encountering new situations and people, the problems were depressingly familiar – the unwillingness of people to co-operate beyond their own fiefdoms and their reluctance to consider change. It was too like what I had left behind. And so I let that pass too.

I was aware that I had long worked with works of art as a surrogate for producing them myself. I had been deeply interested in painting at school but had pursued an academic career instead. It had seemed a safer and more respectable option to me and my parents who wanted to see me get on in the world. I had continued to paint when I could, chiefly on holidays, but what I produced was conventional and never developed. I did what I knew I could do well and took no risks. Now the opportunity opened up of time to paint and push myself further, not with any expectation of commercial success but for the process itself. But how? I was aware of my inhibitions but couldn’t see how to go beyond them. My wife, who had been through art school, gave me the invaluable advice that I had to ‘cover the ground’ and be prepared to make disasters. I took my pastels on the common and drew. I took photos of people in street markets and museums and tried to make paintings from them – with limited success. I realised it wasn’t what I painted that needed to change but how. And this needed a change of attitude. In this I was helped by a teacher at the local life class I joined who had the knack of nudging his pupils in directions they didn’t want to go. Whatever their strengths, he would suggest another medium, a different way of working, going against the grain. It helped to free me from the tight, academic way I had always fostered and which had been reinforced by years of steeping myself in the art of the past.

My new life was utterly unlike my old. It had no structure, no nine to five to shape it and fill the days. There was no-one to tell me what to do, and unless I made an effort to meet people it was much more solitary. All possible ingredients for disintegration. But after years of the contrary, I welcomed and adapted to the shapelessness, acting on impulse, painting when I felt like it, doing household chores (including taking over the cooking) and arranging to meet friends when I needed to. I also decided to take up acting (amateur) and joined a local theatre group. Here was a community I soon felt at home with, a random assortment of people but all with a shared enthusiasm for the theatre. Here I rediscovered the excitement in acting I’d felt as a schoolboy and student. I recalled with a jolt of recognition that the passions of my life when I was young had been painting and acting. Suddenly I was immersed in them again after what seemed a lifetime on hold. They showed the importance to me of creative activity and of performance. With both painting and acting you have to take a risk, a leap into the unknown. You need discipline, to draw on experience, and yet at the same time you have to call on what intuition you have for the right mark, the right gesture, the right tone.

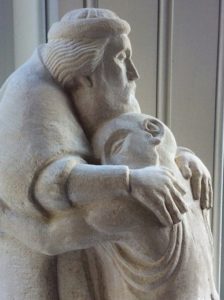

A final break with the past came with our decision to move away from London. We bought an old farmhouse with four acres of land in Sussex not far from Hastings. Before the move we both felt anxiety at moving from our home of twenty eight years and at leaving friends and family. But once there the anxiety vanished in the excitement of renovations and in recovering and replanting the overgrown garden. We converted an outbuilding into studios where we could both work and have room to hold life classes, which we have now done for five years. We discovered contacts in the area we never knew we had, made new friends, and confirmed there is life outside the metropolis. I joined local theatre groups and soon became part of a wider community of enthusiasts. The painting has continued, with occasional forays into exhibiting, and the beauty of our surroundings has given new impetus to what I do. In the last couple of years I have also ventured into stone carving. After learning the basic skills from a stone-carver in Norfolk, I bought some tools and tried my hand. I believe I have an ability to think three dimensionally and so the challenge of chipping away to reveal forms within the block appealed to me. It is a slow activity, by contrast with painting, and physically demanding. But as you work, tapping with hammer on chisel, you begin to sense the stone as almost soft – like cheese – and malleable, as it slowly conforms to the inner vision that guides the hand.

Much in my life has changed in the last ten years. What I do, where I live bear no resemblance to what they were. But have I changed? Fundamentally I am who I have always been, but I feel more fully myself as I am freed from having to conform to what was required of me in my profession, and have been able to explore what really motivates me. What tomorrow holds I cannot tell. There is always the risk that what was new and full of possibility will turn familiar and stale and the joy will go out of it. But experience has shown me that when you make an effort, when you open yourself to an activity, the unexpected happens and you make new discoveries. I trust in this for the future.