Ten years. Ten full, long years in prison so far, with a few still to come. Oh, I deserve every minute of it – I’m just saying, it hasn’t gone quickly. I spent the first eight in HMP Long Lartin, High Security, where the maddest, the baddest and the saddest are sent to fight it out, between themselves, among themselves, inside themselves. It will not surprise you that experiences most would describe as extreme have been in regular supply. There are those you expect, murder, suicide, violence and self harm, hatred and despair: the anguished, furious bellows and screams of men who are hurting, really hurting. Hurting you, maybe. I saw a man trying to cut his own arm off in a workshop once. Another guy, unnerved by an erratic neighbour with obvious, serious mental health problems charged into his cell with a jug of boiling sugar and a table leg. ‘If screws won’t take this fuggin’ fraggle off the wing, I fuckin’ will’, he had announced. He was, gruesomely, as good as his word. But the things you expect become commonplace and the commonplace stops feeling extreme, no matter how spectacular. Only a totally unexpected moment can still get inside a long-term prisoner’s guard.

That’s what happened when I got off the transport to HMP Grendon.

The ‘sweatbox on the van is a grey, upended rectangle with a locked door and a tiny tinted window. It’s just big enough to contain one prisoner, but you wouldn’t want it any bigger. With your hands cuffed and no seat belt, bracing against the sides is the only way to protect yourself from sharp braking, it makes for a miserable journey so it was good to climb out. I blinked in the bleached winter light and looked up.

The sky…

Horizon to horizon, massive and empty, the infinite: so epic in scale it made me reel, and only in that moment did I realise I had waited eight years to see it. My mind slipped back to the place I had left.

In high security, thin wires, hung with orange baubles are strung over the entire prison to prevent helicopter escapes. Believe it or not such attempts have been made. I hardly ever noticed the wires. Sometimes I’d watch a villainous crow try to land on one, feel it flex under its dirty weight, and flap off cawing disgustedly. When it snowed, each bauble would collect a cone shaped topping and the wires glittered with grime. Beautiful, really. Every day I’d walk around the yard, and think nothing of the skinny sentinels overhead. Every feature of the place is intended, after all, to be oppressive, limiting. Everything is functional, and everything’s function reminds the prisoner of how dangerous, volatile and untrustworthy he is. Some men never stop noticing it all, never stop hating and chafing at this brutal reflection of themselves. Some men go crazy. The only way you get through it in fact is to stop seeing it. Then you can stop feeling it. That’s what I did – or so I thought, until I got off that transport.

A tight ball in the middle of my chest expanded, overfilled me; it swamped me. The tension of years drained away, my precious mantle of indifference slipped from my shoulders and pooled at my feet, with my tears. I wept as I felt joy bloom, laced with a shocking twist of homesickness. Homesickness for my former prison. Grief and relief so intense it has become a treasured memory. I never want to forget how I felt, that day, to look up and see nothing but sky.

Adam

HM Prison Grendon

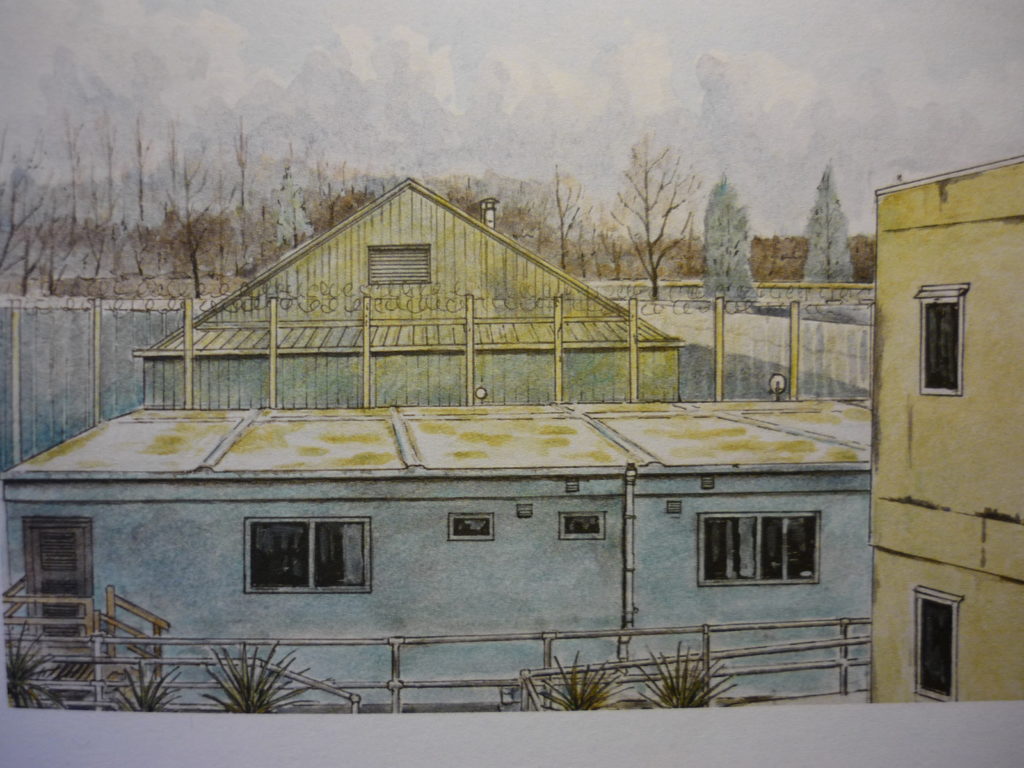

This article and the painting above were seen at ‘Inside’, the powerful exhibition curated by Anthony Gormley of art by offenders, secure patients and detainees, from the 2017 Koestler Awards at the South Bank Centre London from September-November 2017.