‘Mai 68’- Forty years on

“Something happened” during the 1960’s – mainly in the Western democracies, but extending also as far as Mexico and Czechoslovakia. Quite what took place is not easy to discern with clarity. The post-war consensus had begun to lose relevance to a generation which had not experienced the war, had more disposable income, and was looking for new forms of expression, both political and artistic. Forty years later, it seems that the decade in question left western democracies “changed utterly”. It is tempting to extend the Yeatsean reference and say that a “terrible beauty” was born.

Quite when these transformations took place is almost as difficult to specify. In personal terms, Philip Larkin – in a characteristically flippant poem – located it, “Between the end of the Chatterley ban / And the Beatles’ first L.P.” In the French context there can be no such vagueness: “Mai 68” is a phrase which is still in common use to denote a plethora of socio-political changes which exploded during those brief weeks, and which can still arouse passionate differences of opinion. In last year’s presidential campaign, Nicolas Sarkozy even announced his determination “to have done with May 68 for good and all”, a declaration which succeeded in creating a fog of confused and contradictory responses – which was probably the intended effect.

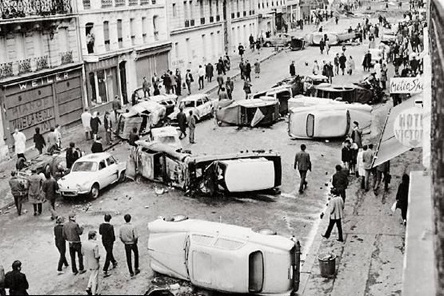

During a few chaotic and delirious weeks a fragile convergence between student rebels and striking car-workers resulted in the biggest general strike in a generation. For a few days the president was absent from the scene, and it looked as though the republic itself was tottering, with increasingly violent confrontations between students and police, filmed, photographed and above all reported live on radio.

However, the government came to an agreement with the unions (the communist CGT did not want to lose its control of radical dissent) and the students were isolated. There was a massive counter-demonstration in favour of de Gaulle, who then called for a general election which was overwhelmingly won by the right.

Now, forty years later, May 68 is again a subject of discussion here, with numerous articles, documentaries and debates which reveal as much about contemporary France as they do about the period in question. From this outsider’s perspective, these events throw a fascinating light on some characteristic features of French culture. Some of the legendary slogans – many still well-known – are very revealing. “Be reasonable, demand the impossible” : even today such assertions have the capacity to irritate – especially those who have continued to emerge from the system of elite lycées and “grandes écoles”, and who go on to occupy the highest administrative positions in both the public and private sectors. (This structure was fundamentally untouched by May 68.) It is hard for foreigners to appreciate the extent to which France was dominated by a centralised elite, almost exclusively male and formed by a rigid, highly normative approach, controlled by “la clarté” and “la logique” . (L’intelligence is not the same thing as intelligence” as Leavis used to say.) I have always felt that surrealism established itself as an important movement in France as a reaction to this dictatorship of “reason”. The 5th republic, introduced after what was essentially a coup d’état in 1958, gave sweeping powers to the president (France has with some justice been described as an “elegant dictatorship”) Media were largely orchestrated by the state, and criticism of the government was often stifled, with the honourable exception of “Le Canard Enchainé” which is still a thorn in the flesh of today’s politicians.

This supine, ordered conformism was radically challenged in May 68, and although the political system seemed if anything confirmed in its hegemony, many features of an “alternative” culture present today can be seen as emerging from this period: a critique of consumerism, advertising, authoritarian family relations, rigid educational and cultural practices and so on. (These in turn have inaugurated new rigidities and orthodoxies of course). In other words, it was essentially a cultural revolution, leaving the political and economic structures largely unaffected: in many respects France is still governed by a small elite drawn from a tiny minority, with the same values of “clarté” and “logique”.

The discussions here have largely centred on whether these cultural changes have been “good” or “bad”: for example whether the crisis in education, the collapse of authority, alienated youth, the erosion of the family etc. can be traced to May 68.

Personally, I feel that the explosion of new values – however excessive, even absurd – was itself a positive. As Blake wrote: “Without contraries is no progression. Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate are necessary to human existence.” For all their manifest excesses and absurdities, the events of May 68 gave voice to alternative values which are just as necessary today. To quote Blake again: “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.”

Julian Arloff