I live in Oxford, on a street which is about two minutes walk from one of the large municipal parks, and sometime near the start of 2001 it was announced that the band Radiohead would play a homecoming concert in the park. It was to be their only UK date that year, and they hadn’t played in this country for sometime. There was the usual scramble for tickets when they went on sale, but friends and I managed to get hold of some, and the day of the gig was eagerly awaited.

The day started relatively well – my friends all arrived more or less on time, and we got into the park without too much fuss. It was then that the first grey cloud decided to set the tone for a day which was damp in almost every sense of the word. The support acts, whom we were looking forward to seeing, all came and went with most of them putting in something approaching a lifetime’s worst performance. As it happened they were all outshone by the wit and showmanship of a man who was born 80 years ago (Humphrey Littleton had played on Radiohead’s most recent release and was invited along with his big band). After the final support act had finished, the music being played over the tannoy changed from familiar, popular music hits that the fans knew and were singing along to, to bizarre, crackly 1920s jazz. The rain became heavier and the bizarre queuing system for the beer tent (queue up once to exchange your money for a ticket, queue up again to exchange your ticket for a drink) had put paid to the idea of driving the rain away with alcohol.

The niggling feeling that this might not be the greatest gig of the band’s career, but in fact a cold, dull trudge through new material that nobody was really sure was up to much, started to build.

People were keeping half an eye on the stage to see when the road crew would retire to the wings and make way for the band to come on.

And then it happened.

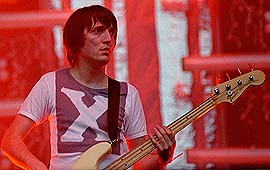

Suddenly there was a rising cheer from the front of the crowd, and the bass player sprinted from one side of the stage to the other, picked up his guitar and played the opening riff to their song “The National Anthem”. It’s strange that I clearly remember him sprinting – not walking, loping, jogging or ambling, but sprinting – to the other side of the stage, but I do.

An entire field’s worth of people were suddenly lifted out of their gloom and deposited firmly into an entirely different groove, by one man, his bass guitar and a heavy, insistent, thumping bass riff.

A shock. The rain had gone. In fact, it hadn’t been there all along – just a figment of the imagination. The sound coming from the PA speakers was no longer scratchy, uninteresting and as grey as the weather. It was ominous, brooding, exploding and powerful. The song built samples of voices played backwards as well as forwards, funereal New Orleans trumpets, the overbearing bass riff and lyrics that were difficult to discern, lyrics which gave an impression of something that they didn’t describe. The crescendo was a mess of noise, unlistenable in a way but evocative of something very familiar.

And then it was over. And it’s raining again. And I wonder where James has got to with our drinks.

The second song starts and, without any words from the singer, the lead guitarist breaks straight into the main riff. A trick that has been used for years and years by rock bands to try and maintain the incredible, yet very fragile power that very few songs can generate. One wrong note and it’s gone, but if you can get a couple of your best songs in right at the start of the set, while people are still eager, you have some points in the bank right from the word go. A goal in the opening ten minutes.

It doesn’t work. The guitarist gets far enough into the riff to give away what the next song is, the drummer starts playing the telltale sleigh bells and the rest of the band are about to begin, when suddenly the riff stops and the guitarist violently waves a jerky “stop” signal to the rest of the band. 40,000 people in a field are, for a moment, silent. The singer walks to the microphone and simply says (in an impersonation of a popular comic character of the time), “Bugger”. It is more human, more simple than pretty much anything else that could have been said. It instantly dispels the idea that the five people stood before you on an enormous, purpose built stage, flagged by lights that you can feel the heat from fifty yards away, are anything other than some talented musicians that struck it lucky. They too suffer from stubbed toes and bruised egos, and despite all attempts by the vast number of people assisting with that day’s event, they had been shown up to be, heaven forfend, real people.

The audience laugh and it seems that the singer is genuinely relaxed in this tricky situation. A spare guitar is found and, unnecessarily, given that everyone in the place knows exactly what the song to be played is, the singer announces in an, “I’ve already failed my driving test after the first bend, so I might as well just enjoy the next half an hour,” voice “Alright, this is ‘Airbag’”.

They start again. This song is about being in a car crash, and the exhilarating feeling of actually being alive. Utterly absent moments before the crash, it is suddenly so apparent immediately afterwards. “In an interstellar burst, I am back to save the universe,” go the lyrics. And they are. Aside from a warm feeling of friendliness towards the band – who hasn’t been in one of those awful situations and had to dig themselves out of it? – we’ve lost ourselves in their music again.

The evening continues in much the same vein – I am often taken far away by the songs, but feel as though I come close to touching something in myself through the music. “Yes,” I say to each song, “That’s exactly how it feels”. I couldn’t possibly have hit upon that formulation, but I don’t need to – this music does it for me.

Towards the end they play, “Pyramid Song”. Much has been written about this piece of music – shimmering strings over an ethereal sounding piano, lyrics said to be inspired by Dante’s Inferno – but as I look into the sky above me while it’s playing, I notice beams of light from the stage forming a pyramid above me. Picking out the drops of rain in the light beams, I suddenly find that I don’t really know where I am. I don’t feel wet, and I hadn’t remembered that it was raining – perhaps I’m actually indoors in some sort of temple? Perhaps I have “Gone to heaven in a little row boat” (as the song’s lyrics suggest). Wherever I am, I don’t think it’s in the park, yards from the front door of my house, listening to pop music.

It ends more slowly than it began, winding down with the predictable round of encores. When it’s finished, the entire crowd seem to be buoyed by something. Have we really all shared a common experience, and been touched in ways that we’re not accustomed to, yet unknowingly crave?

I give a lift home to some friends of friends. It’s a half an hour round trip, but they will never get a taxi now and it must be a six or seven mile walk. One of them has to ride in the boot because there’s not enough room for them all – he doesn’t mind being in the dark for fifteen minutes since he can hear the muffled voices of his friends, and tries to join in the conversation at points. I wouldn’t have minded doing two trips.

Then I go home and talk to the friends who are staying the night at my house. I don’t feel tired when four o’clock in the morning rolls round, but I go to bed anyway, still thinking about tens of thousands of people singing, “Phew for a minute there, I lost myself” along with the band.

Alex Horwill