“. . . Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!”

The Red Queen, Alice in Wonderland

Sport has altered quite a lot since I first commenced youthful training, trotting barefoot around a field, and for a time innocently consuming fresh raw milk and raw eggs to increase my stamina. There is now substantially more invested in sport by corporate, national and international finance than sixty years ago. There is worldwide twenty-four hour media coverage, manipulative institutional politics, modern scientific training, technology, and much else. The dominating direction is increasingly oriented towards the getting of results. However, on occasion someone comes along with a natural, unspoiled skill and for a short time lights up the stage; doing so while going in the opposite direction, paying attention to good use and not bothered about outcomes.

Before the magnificent runners out of Ethiopia and Kenya caught my attention I had my heroes. Those who inspired and with whom I ran in my mind were Paavo Nurmi called the “Flying Finn.” He was someone out of a fairy tale, and his influence over distance running was so elusive and complete he was also known as the “Phantom Finn”. The legendary Jesse Owens (USA) could not be missed. Subsequently there was Ron Clarke (Australia), Jim Ryun (USA) who in his youth prayed, “Dear God, please help me… find a sport I am good at.” Latterly there came George Perdon (Australia) who in 1973 ran from Freemantle to Sydney a distance of 2,987 miles (4,807 kilometers) in 47 days.

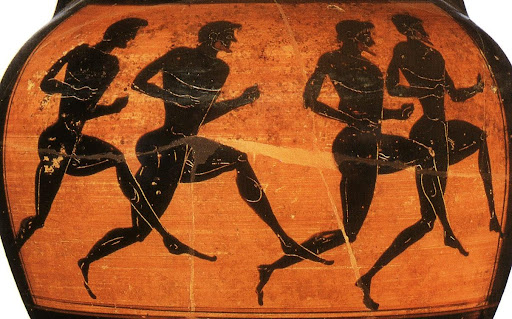

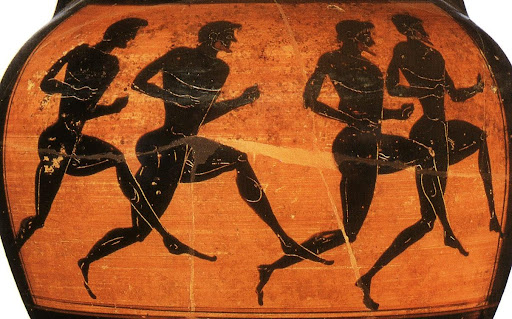

There were the runners, not from the fairy tales, but from myth, among them the Aboriginal runners of the Dreamtime, The Lung-Gom-Pa Runners of Old Tibet of whom it was said, they could run over 200 miles without rest in a single day. Their intensive spiritual training was not to win races, but similar to the marathon monks of Japan, its purpose was to attain enlightenment. Pheidippies, ran from the battlefield at Marathon to Athens to announce Greek victory over the Persians, a distance of 25 miles. However before this he had run from Athens to Sparta to seek help from the Spartans, a distance of 150 miles. After a short catnap and some food he ran back to Athens, in all 300 miles in four days. Pheidippies was one of the mysterious hemerodromos: men beyond competition, known as day-long runners, who carried out their duty as runners but whose running was ultimately in service to the sacred.

Running high, Zen in Art of Running, the Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner… I read all I could about running. The chemistry involved in the sport, the part played by endorphins, the body’s homemade opiates and their relationship with endocannabinoids, the body’s natural version of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). This intricate interplay that can lead to euphoria and, without due care, to running becoming desperately addictive. My practice, such as it then was, was not consistent, neither was it intelligent. This was brought home to me after running fifty miles through a warm day, by the end of which I was hobbling, and for some weeks thereafter needed the aid of a walking stick.

It slowly began to dawn upon me running was only a means whereby, a preparation for something Other and not an end in itself. Preparation for a place where there is no running towards, or away from, a place requiring quiet, stillness, verticality. A vivid human place where it is no longer, I am running, but being run, no longer I breathing, but I being breathed.

In the preliminaries to the Diamond Sūtra it is indicated there comes a time to listen to the sutras. This does not mean listening now and then but to attune regularly, and for this three things are required.

A true teacher

A true teaching, and

True study.

It took sometime before encountering the first two and so much later to come towards the beginning of the third. There one may, as T. S. Eliot wrote in the Four Quartets,

“… arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.”

A soccer professional whose stark endeavour was to mark George Best in his prime stated, “trying to mark him twisted your blood.” The journalist Patrick Barclay said of Best: “In terms of ability he was the world’s best footballer of all time. He could do almost anything – technically, speed, complete mastery of not only the ball but his own body… his balance was uncanny, almost supernatural…” one has only to watch the intelligent movement that manifested through Best during his period with Manchester United to confirm this. However I would question he had complete mastery of his own body. His subsequent sad, somewhat tragic decline revealed he had little mastery, but what he undoubtedly had for a time, was a remarkably fine, instinctive centre of movement.

In golf there was the legendary Bob Jones who in life as in sport intimated that one should play not only by the rules but also the etiquette of the game. Jack Nicklaus of whom one of his opponents, stated after a major tournament which Nicklaus won, “Well, we were all playing golf but I don’t know what Jack was playing!” But while eyes are on the players such as Tiger Woods or Michelle Wie, how many notice the contribution and influence of the caddie or the coach. James “Tip” Anderson born with the craft of golf in his blood, and with his understanding of weather and psychology helped Arnold Palmer and Tony Lema win British Open Championships. Claude ‘Butch’ Harmon coached Tiger Woods to eight major titles and Greg Norman to his success in the 1993 British Open. Tiger Woods experienced difficulty finding the elevated level of his own game after separating from Harmon. But his former coach once stated, “I start from the premise that old habits are hard to break.” 1

John Curry, one the most gifted of dance-ice-skaters, who endeavoured to manifest in movement many facets of his exploration, was instructed in his early years of skating “don’t be graceful”. Lester Piggott (UK) sometimes won against all odds “in the sport of Kings.” He was amply supported in his endeavour by the remarkable ‘eye’ of Vincent O’Brien, and the shrewd investment of Robert Sangster, and John Magnier. The “brethren” (as the latter trio became known) had a revolutionary effect on the world of horse racing. Bill Shoemaker (USA) who rode his first winner aged fifteen in 1949. “At 7st, he was always 20 lbs lighter than his British counterpart Lester Piggott, while his 2 quarter-size boots and tiny legs — only twelve inches from the knees down — made inexplicable his featherlight balance and centric control on a careering thoroughbred.”2 Fred Archer, celebrated horseman infused with an aura of mystery but little known today, rode 246 winners in 1885 and 2,746 between 1869 and 1886 in a time without helicopters, automobiles, audio-visual media or business agents.

In cricket we had Donald George Bradman, nicknamed “The Don” (Australia). His unparalleled test batting career average of 99.94 was extraordinary. There was the fluid gracefulness of Viv Richards (West Indies), and Sachin Tendulkar (India), who while in form was enabled “to release strokes down the ground so sweetly timed that they were almost silent.”3 The remarkable Gertrude Ederle (USA) who in 1926 became the first woman to swim the English Channel along the way breaking the men’s record for the crossing by two hours. She subsequently devoted much of her long life to teaching deaf children the art of swimming. Leônidas da Silva (Brazil) of whom it was said, “He was as fast as a greyhound, as agile as a cat, and seemed not to be made of flesh and bones at all, but entirely of rubber …and compensated for his small height with exceptionally supple, unbelievable contortions and impossible acrobatics.” The intelligent aim and balance of Édson Arantes better known as Pelé, the agility of Manuel Francisco dos Santos (Garrincha), both instinctively knew how to play the unique Brazilian ‘futebol-arte’ of winning through apparent loss.4

In athletics the fine distance runner Haile Gebrselassie eventually gave way to an athlete of powerful closing speed, his fellow Ethiopian Kenenisa Bekele. Fanny Blankers-Koen (Belgium) who “had sensational spring in her long legs” won four gold medals at the 1948 London Olympics, set 20 world records at eight different events and opened a new trail for women in sport. Roger Bannister, maybe not the greatest runner, and around whom an idealised and inaccurate view has grown that he rarely trained for more than thirty minutes a day, and simply turned up to run the first recorded sub-four-minute mile5. There was the raw talent of Emil Zatopek who represented Czechoslovakia and whose running style was described in the New York Times as “the most frightful horror spectacle since Frankenstein.” He won the 10,000 metres in Helsinki in 1952, then to give himself something to do entered the 5,000 metres, having won that he nonchalantly showed up for the marathon. The fact that he never had run one didn’t bother him. He introduced himself at the starting line to Jim Peters the then world record holder, and when the race commenced proceeded to copy him until he was ready to strike out for his third gold medal in eight days.

Babe Ruth, Joe Di Maggio in baseball6, Steffi Graff, Roger Federer in tennis, and whereas Federer never had the sheer physical capabilities of Rafael Nadal or Novak Djokovic, he was in my view the finest player of the three. There was Francis Joyon (France) in sailing, Steven Redgrave (UK) rowing, Ayrton Senna (Brazil), Michael Schumacher (Germany) in Formula 1 motor racing.

There are levels, so too in sport, and in the ‘sport transcendent’ there are those truly remarkable explorers who swim out alone into the deepest oceans, along the way meeting with their ‘demons’, and the ghostly lure of sirens, who will, if heeded, draw them down into a ‘peaceful’ watery grave. Others like Johanna Nordland, who after a severe accident, and in search of healing entered the cold water world of swimming under ice. Here she related, “there is no place for fear, no place for panic, no place for mistakes, complete trust in the self is required.”

Some aspects of the mentation of modern sport may be gleaned from James Lawton when he referred to the Bernabeu stadium in Madrid as “one of the great Temples of the game.”7 Phil Vickery offered further insight when he equated rugby with war, fans baying for blood … and the effort of training as being “flogged like animals.”8 This attitude, although understandable, is a flawed, “one natured” perspective of sport which can lead to the “win at all costs” brutality and ruthless manipulation of the psycho-physical organism. Many young people suffered to the extreme in their gymnastics and athletics training in the former German Democratic Republic, and the Soviet Union. Particularly in gymnastics the onset of ovulation in young women was suppressed, or pregnancy (followed by abortion at what was considered the appropriate time) to enhance blood supply was built into a female athlete’s preparation.

There was, and I suspect, still remains in some parts, the practice known as blood doping in which up to a quart or more of blood is extracted and frozen while the athlete continues with training to rebuild the blood to a normal level. Shortly before the sporting event red blood cells from the extracted blood are transfused back into the athlete, thus increasing the body’s haemoglobin level and oxygen-carrying capabilities which enables greater endurance. Blood doping remained legal until 1986, the same year that a synthetic version of the hormone erythropoietin (EPO) was produced. EPO, a single injection of which, offered the same benefits as blood doping, was quickly banned9. However ways around such bans can be readily traversed, such was the case with Lance Armstrong (USA, cycling) who between 1999 and 2005 cheated and intimidated his way to winning the Tour de France seven times. He was rather belatedly stripped of these titles.

Brian English the British team doctor at the 2004 Athens Olympics indicated that Paula Radcliff could have died had she continued and tried to finish the marathon, however this did not satisfy some of the more rabid British media, most of whom I suspect had never run a competitive mile in their lives. Anyone (in spite of the best and most thorough preparation) who has run a long rising distance in hot weather understands something of the deterioration that overwhelmed the distressed runner. There is more appropriate postural behaviour in stopping than dying for a gold medal.

I have observed many players over the years participating in individual or team sports, some like the high jumper Bill Fosby at the Mexico Olympics broke all the then applicable techniques and transformed the game. Others like the English cricketer Geoff Boycott, without too much raw talent persevered, consistently practised and gradually brought a formidable shape to their use. On occasion the movement and poise like the former All Blacks player (New Zealand, Rugby Union) Grant Fox evokes a call to observe more closely.

The play of names and their respective games could go on for many pages whether it be American “gridiron” football, basketball, bowling, free-climbing, hockey, volleyball, surfing, pelota vasca10, rowing, squash, to mention but a few. But who among the participants of sport understand what may in effect be happening, and carry the knowledge of those universal principles into daily activities long after their names are eroded from the arena?

In December 2003 I was having a conversation with Walter Carrington11, he spoke about Johnny Wilkinson and the drop goal that secured the English Rugby Union team their victory by a “whisker” against Australia in Sydney. He said it was worth watching for the rotation of Wilkinson’s spine. I asked him if he thought the player knew what had actually happened. He replied “probably not, and if he did he would only muck it up”.

I have rarely heard participants or commentators acknowledge, let alone explore, that there may be other forces at play in sport as in other matters which are much bigger than any individual, team, or nation which also affect the outcome. It is most often the case that all manner of managers and players who do not concern themselves with, or wish to understand why it is “It comes and It goes,”12 stay about too long, attribute to themselves powers that they do not have, as a result ego’s and/or salaries become grossly inflated.

The laws governing the universe apply in all earthly endeavours. Sooner or later the best individual or team arrives at a point of critical deflection and begins to decline. This is the moment to retire or apply needed corrections. Sir Alex Ferguson while manager of Manchester United instinctively understood this, as he did other psychological aspects of the soccer game. The rivalry moulded in measured mutual respect between both he and Arsenal’s manager Arsene Wenger brought a wealth of study, not least to see the ‘Fates’ gave more in those days to United than to Arsenal.

While visiting Dublin in 1986 a friend invited me to watch a Gaelic Football match at Croke Park, the GAA’s (Gaelic Athletic Association) premier stadium. The game was between Counties Kerry and Meath, the latter team was young and on the way up. The Kerry team on the other hand had been foremost in the top echelon for some time, but it was a team then beginning to enter the twilight of its descent.

The game unfolded with the young players of the Meath team running ‘fast and furious,’ getting to the ball first and sending it on its way. Come half-time I took note of the fact, the Kerry players though being outrun were not being outplayed and on the scoreline were not that far behind, and this while playing against the wind. The second half commenced and play went as with the opening half, but about ten minutes into play I sensed a change in the atmosphere. I can best describe it as a light came on above the playing area of the stadium and energy descended from it, suffusing the players of the Kerry team. For the ensuing fifteen minutes those players were unsurpassable. The ball came effortlessly to their feet, their hands, and just as effortlessly the scoreline rapidly changed in their favour.

One could put what occurred down to training, experience, skill, the quality of individual players such as Eoin Liston or Jack O’Shea, the collective oneness of the team, good management13. Indeed all of these factors and yet there was also the appearance of that something Other, Unknown. What occurred was not the product of imagination, of this I had no doubts, and just as spontaneously as the light came on it switched itself off. Thereafter the game reverted more or less to its initial pattern. The Meath men continued to participate to the best of their abilities but the ‘force’ was not with them on that occasion.

For some time after I reflected on what I had seen and came to view it as something of a miracle. A miracle for me is both something profoundly simple and practical, involving levels. In this instance the manifestation of energy from a higher level upon a lower. It is an energy, that however much one can try to do so, cannot be manipulated, and just as a properly prepared archer or golfer can, by their presence, actively participate in the trajectory of an arrow or golf ball after it has been loosed or hit, they cannot do the action of IT, the Unknown14.

In youth I watched games that were tribal and savage, often for one reason or another degenerating into violence not only involving entire teams but many of the spectators drawn in as well. Such mayhem left a strong impression. Where was the required discipline, especially of emotion? It was said to me by a wise and practical man, “can you be passionate about your country but not be identified?” Applying this counsel not solely in sport but in much else requires a light, persevering practice. A few who have learnt something fundamental and enduring continue to explore and as result in their later, elder years, long after they have left the spotlight become refined, elegant players in a much greater game.

In the poignant Swedish film My Life as a Dog15 the young boy Ingemar who without a father and with his mother dangerously ill, is sent to spend some time with his uncle. His uncle befriends him and as they are sitting together a day before a local soccer match. The uncle says to Ingemar:

“Right, you should have the ball here. In your head. So you don’t have to chase it. You have to be the ball. Then you stand where you know the ball is going to come. You’ll see tomorrow.”

The match day comes and the uncle is in goal wearing his number one jersey. He gets a whack from the football and is sent spinning. Later on the way home with his nephew he says with some wonder about the incident:

“No I got it right in the head, groggy. Didn’t see it. Right in the head.”

That humorously illustrates a great deal of what actually goes on both on and off the playing field.

Traol Chú Mhara

_________________________

Johanna Nordblad (Swimming under the ice).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=leqyKxbOxTA

Stephen Redmond (The first swimmer to complete the oceans seven challenge).

_________________________

12 Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean won the gold medal at the Sarajevo 1984 Winter Olympics. The pair became the highest-scoring figure skaters in the sports history for a single programme. They received twelve perfect 6.0s and six 5.9s., which included artistic impression scores of 6.0, from every judge, after skating to Maurice Ravel’s Boléro. Interviewed, shortly after finishing their routine Christopher Dean said, “I do not know what happened out there, It came and It went.” And so it was as they skated together, by moments It came and It went.

After ten years as professionals, Torvill and Dean decided to return to the amateur arena for the 1994 Olympics in Lillehammer, Norway (following a change in eligibility rules).

Although they skated well and with the crowd behind them, it came as some sadness to me that they had not explored ‘skating from the known into the unknown’. They may not have won had they done so, but it would have left a wondrous impression upon those who had some feeling for such an effort. The judges placed Torvill and Dean third, giving the gold medal to Oskana Grishuk and Evgeni Platov of Russia who deserved it.